A 61-year-old man, who had recently emigrated from the Ukraine, presented to his primary care provider with a chief complaint of painful oral lesions and weight loss. The patient described the gradual onset of a severe sore throat and mouth pain three months earlier. Originally, he attributed his symptoms to an upper respiratory infection but became concerned when his symptoms did not resolve.

He reported that the pain had worsened over time and that he was now barely able to swallow solid food or tolerate acidic beverages due to considerable discomfort. His son, who accompanied him to the appointment, had also noted weight loss.

The patient denied any concomitant symptoms, including fever, cough, night sweats, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, or concomitant rash. His medical history was remarkable only for stage 1 hypertension, which had been well controlled on hydrochlorothiazide 12.5 mg/d for the previous three years. However, the patient had received only minimal preventive health care while living in the Ukraine. His family history was unknown.

One week earlier, the patient had seen a dentist complaining of mouth pain, and was referred to an oral medicine specialist; this specialist, in turn, referred the patient to a primary care nurse practitioner for lab work to confirm the suspected diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.

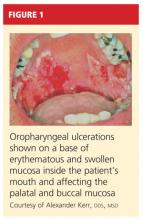

On physical examination, the patient appeared older than his stated age. He was a thin, mildly ill–appearing man, afebrile and normotensive, with heart rate and respirations within normal limits. However, intraoral examination revealed multiple oropharyngeal ulcerations of varying size on a base of erythematous and swollen mucosa on the inside of the man’s cheek and palatal and buccal mucosa (see Figure 1). On his upper back, two round, crusted blisters were noted in isolation (Figure 2). The remaining findings in the physical examination were unremarkable.

Based on the patient’s physical exam findings and clinical guideline recommendations regarding chronic oral ulcerations of unknown etiology,1,2 the patient was scheduled for a cytologic smear to be performed by oral medicine, followed by a gingival biopsy for a direct immunofluorescence test and routine histopathology.3 Unfortunately, due to extensive involvement and concern for possible mucosal shredding, an oral biopsy was not deemed possible.

However, the oral medicine specialist, because he strongly suspected pemphigus vulgaris, recommended testing for circulating autoantibodies against the antigens desmogleins 1 and/or 3 in the epidermis, which are responsible for cellular adhesion. (A positive test result supports, but does not confirm, a diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris.4)

Additionally, baseline labs were performed for signs of systemic illness, including infection, anemia, and liver and kidney disease. Frequent monitoring was conducted for steroid-induced symptoms of elevated blood sugars; the primary care provider was responsible for monitoring the patient for weight gain and steroid-induced psychosis. The patient was referred to gastroenterology for a colonoscopy to ensure that his weight loss and anorexia were not the result of gastrointestinal malignancy. However, the patient declined this test.

DISCUSSION

Painful oral lesions can have numerous etiologies of varying severity and complexity, including herpes simplex virus infection, aphthae, lichen planus, erythema multiforme, squamous cell and other oral carcinomas, primary HIV infection, lupus, and pemphigus. Differentiating among these conditions requires a careful medical history and complete physical exam.5

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common variant of pemphigus, a group of chronic autoimmune diseases that cause blistering and ulceration of the mucous membranes and the skin.6 From the Greek pemphix (bubble), PV is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent,6,7 usually occurs in middle-aged and older persons, and occurs about 1.5 times more commonly in women than men.5,7 Until the introduction of systemic steroids, pemphigus was often a fatal disease. Significant mortality still exists, mainly as a result of infection or adverse reactions to medication therapy.5

In patients with PV, flaccid bullae are formed on the skin in a process called acantholysis, in which epidermal cells lose their ability to adhere to one another. This results in rapidly expanding, thin-walled blisters on the oral mucosa, scalp, face, axillae, and groin. The blisters burst easily, leaving irregularly shaped, painful ulcerations.4 Painful oral mucosal membrane erosions are the first presenting sign of PV and often the only sign for an average of five months before other skin lesions develop.3 These lesions are noninfectious.

To make a definitive diagnosis of PV, clinical lesions must be present, with a confirmation of histologic findings, acantholysis on biopsy, and a confirmation of autoantibodies present in tissue and/or serum.4 (For proposed detailed diagnostic criteria, see table4,8.)

Initial misdiagnoses, which often lead to delayed or incorrect treatment, usually include aphthous stomatitis, gingivostomatitis, erythema multiforme, erosive lichen planus, herpes simplex virus, and/or oral candidiasis.3